I have worked for about a year for one of the key customers of our Shanghai branch, I consider it a success story of Agile development.

The challenge

We have a Party A vs. Party B relationship with our client, we play by their rules.

Our customer is not interested in software technicalities, and more importantly, is not interested in understanding continuous delivery, or even best practices for gradual improvements. And I don’t blame them! According to their internal rules, any large expenditures in IT must be approved by their purchasing department, a department that is even less interested in the internals of the project.

They must view the project as a typical waterfall, with a well-defined scope, deadline, and cost. Intermediate releases or feedback loops are nice to have.

So, our business model and relationship with the customer doesn’t allow for us to easily charge how our customer will work (they are a large corporation), all of this means that we must:

- Create budgets in advance with fixed scopes and deliverables, and assume the risk of delivering a low-quality software, or going over budget if taking longer than expected.

- Have a timeline in advance for most deliverables of the project: this is not quite compatible with the most orthodox agile approach.

- Keep internal improvements “to ourselves”, only the most disrupting internal technical improvements (e.g switch major versions of frameworks) are allowed in the budget. Our customer would typically not pay for changes which are not “customer-facing”.

Strategy

We have had a long collaboration with the customer, which allows us to keep a protected position compared to other competitors.

Over the years, we found that breaking projects into pieces worked, even at the purchasing level.

Minimum viable… project?

We often spend time with the customer, understanding their pain points and ideas for the upcoming needs. We collaborate closely with them in drafting a plan on what the future needs are. Our key is that we know Agile so we know that a project can be split into several projects.

Even before the bidding process starts, we are able to conceive our project as in phases, each with their own cycle of delivery and plan (much like agile). Certainly, we don’t get to have a billed project as small a single iteration, but we do get close. Internally, we use an iteration of 2 weeks, and we typically sign a “project” of 4-8 iterations (2-4 months).

If we identify that the upcoming project is larger than that, we often advise to split it, or at least create different work packages for each component of the application which can be invoiced separately.

Continuous process improvements

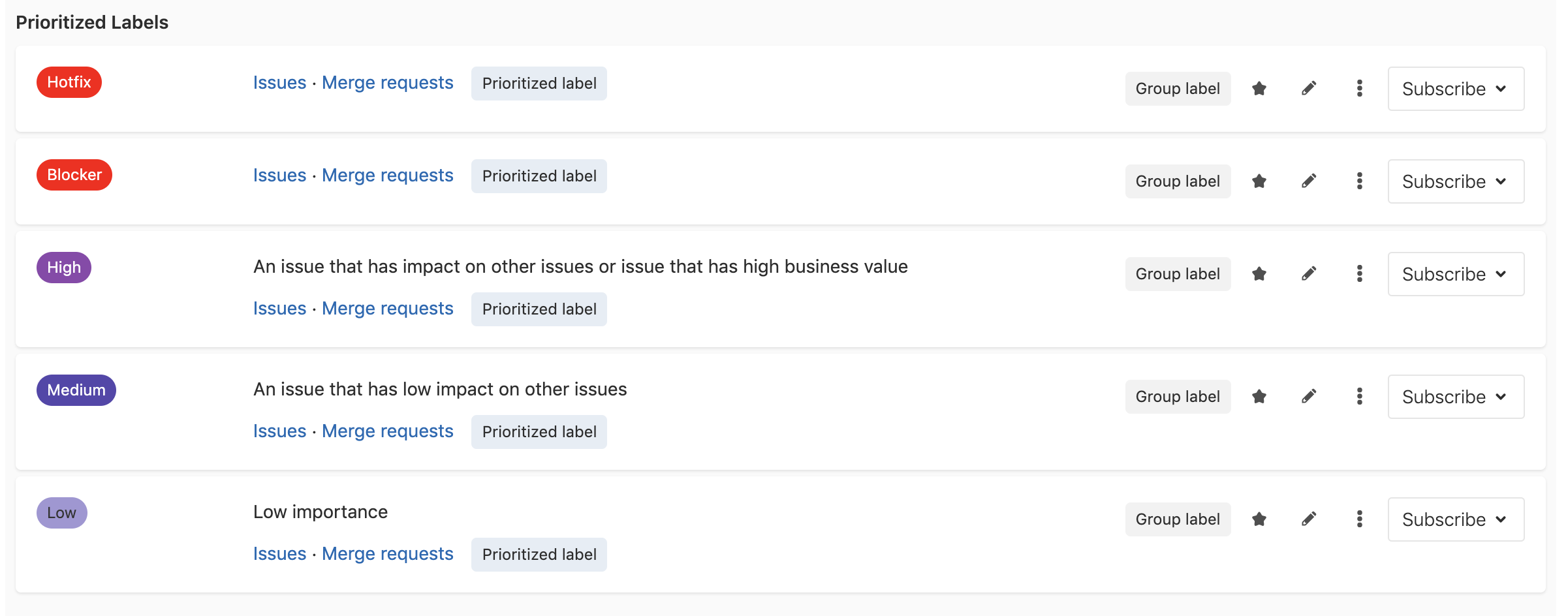

It would not have been possible to push a whole SCRUM training to the management team, so we introduced the more relevant topics one meeting at a time. I consider two aspects of Agile as very important to introduce early and often: prioritization and delivery time.

Prioritization seems to be obvious to most people, but if asked, any customer would label most issues as of “critical” importance. So here, the key is to force them to prioritize by comparison: Is this more important than that?

This was not an easy process at the beginning, but soon, the whole team could reserve higher priorities to only really pressing items.

A 2-week cadence of delivery times, had to be enforced strongly by our team to the customer, they had become accustomed to “immediate delivery” by other vendors but once established it became second nature.

Tactics

Once the project is split, we use the more usual Agile processes inspired in Scrum.

Our Team

Our team consists of 5 people with relatively well-defined roles:

- 2 back-end developers

- 1 front-end developer

- 1 account manager & business analyst

- 1 project management officer & occasional exploratory tester

- 1 release manager/scrum master (me)

Iterations setup

We use Scrum with iterations/sprints of 2 weeks, we organize our work so that in each iteration we can make a full delivery and go-live.

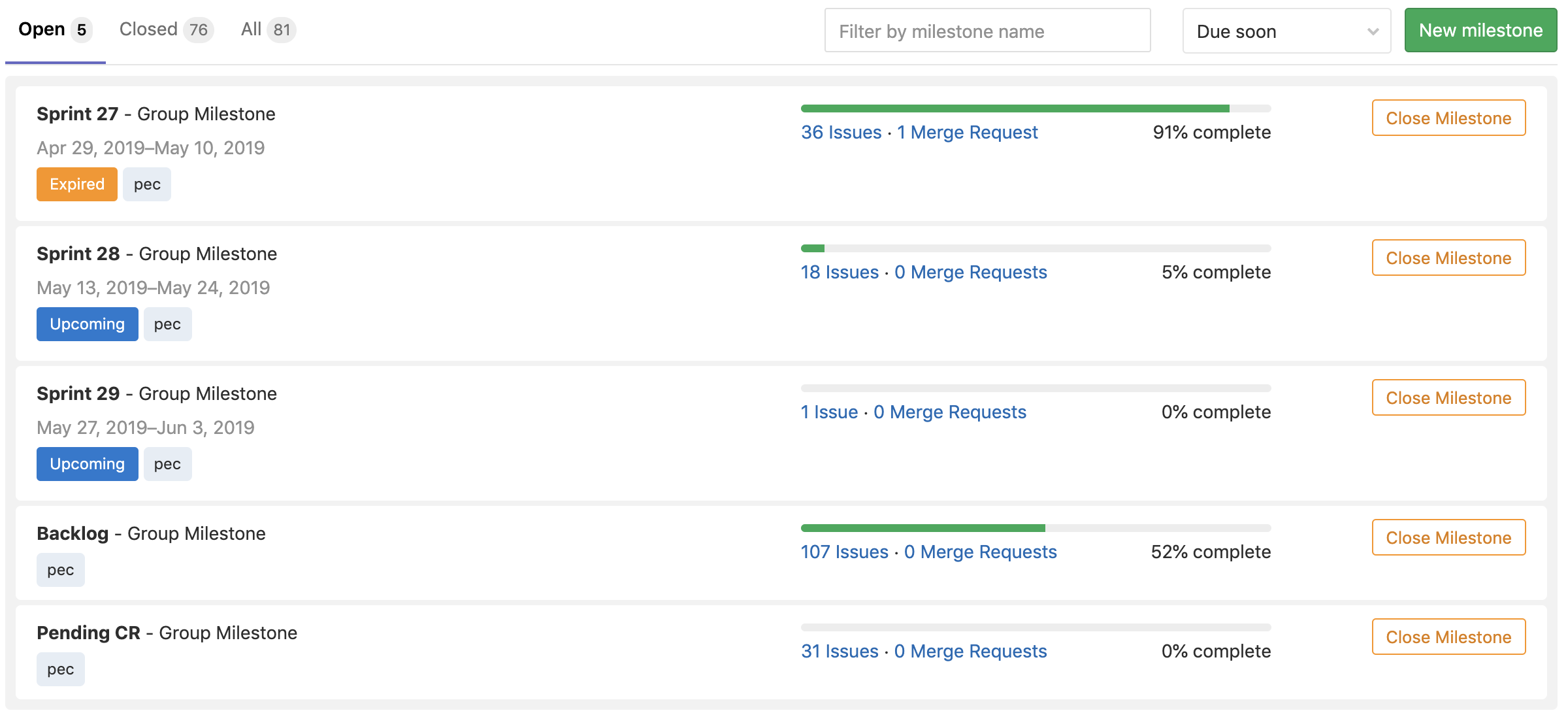

This is an example of how our active iterations look as Gitlab Milestones:

This is the typical timeline of our iterations:

| Time | Activity |

|---|---|

| 1st Monday | Iteration Planning: Select items from the backlog and evaluate the scope and goals of a sprint. |

| Every afternoon | Daily Stand up: Our team is distributed, so our meetings are often around 30-40 mins, as no more communication is done during the day. |

| 2nd Monday | Backlog / upcoming tasks refinement and estimation, no fancy poker planning, just common understanding of the tasks. |

| 2nd Thursday | Deploy to the staging environment, manual smoke tests |

| 2nd Thursday or Friday | Deploy to production, sometimes this deployment is delayed to next Monday if we consider it a “risky” one. |

The exact release time is always a topic of discussion, however, we typically finish our delivery on Thursday’s and deploy… I don’t see a need to have an exact schedule we must follow at all costs.

Some additional activities which are planned ad-hoc include:

- Meeting with the customer to discuss upcoming deliveries and timelines, usually only part of the team attends.

- Meeting between me and the business analyst to have the first idea of the size of tasks, and initial spec before a Backlog refinement.

Some game rules of our iterations

- One issue cannot belong to several iterations.

- If an issue cannot be completed in an iteration, it must be removed as soon as possible.

Our issue management

Our project management tool is Gitlab. This was not a calculated choice, but the result of having it already available as a code repository, and slowly adopted because it was easier to draft our issues and improvements directly there.

I don’t think the Gitlab issue tracker is the true reason for the success of the Agile setup, but it does help to reduce some of the fraction of tool switching and quick backlog refinement and issue tracking that lives in the same place as our repository.

Task execution flow

Our tasks move from one “Milestone” to the next:

- Pending: Tasks that have not been confirmed or specified.

- Backlog: Tasks that should be done, at a future date.

- Sprint N: Current sprint, about to be executed.

- Sprint N+1: Postponed for next sprint, because time was not enough.

The tasks typically make it in to iterations according to priority:

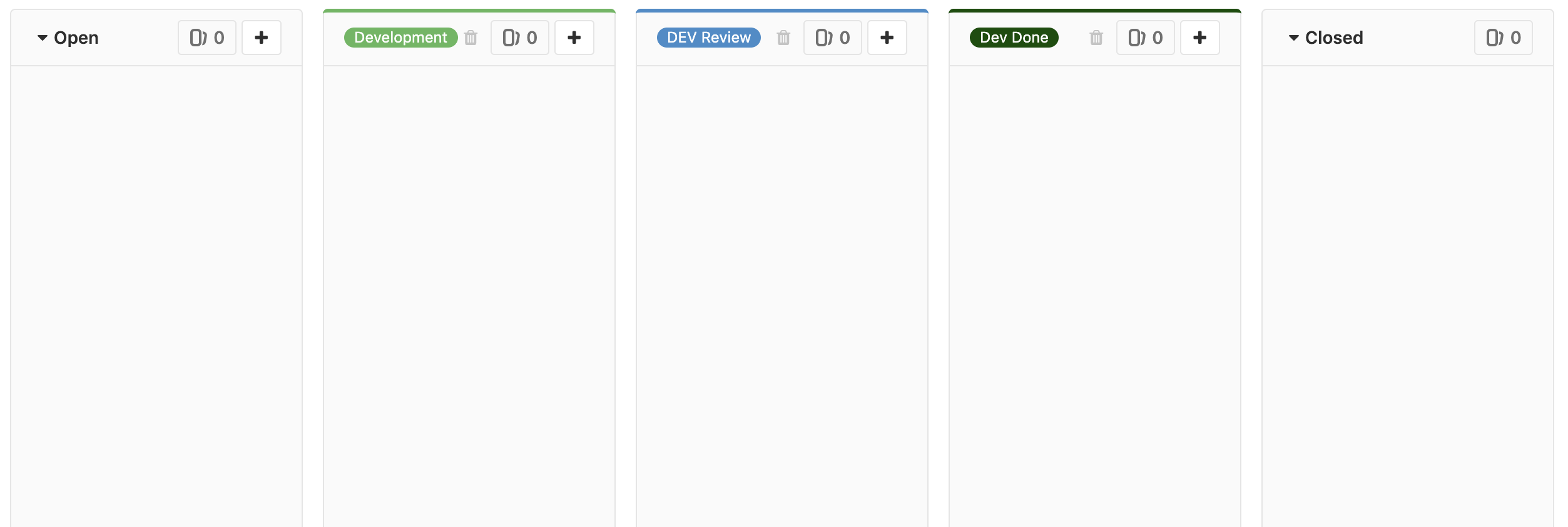

And inside the current iteration (Milestone) as so:

- Open: Tasks that have not been confirmed or specified.

- Development: Task has been picked up by someone on the team.

- Dev Review: Task has been done, and must be reviewed, usually a code review by another team member.

- Dev Done: Code for the task has been merged and can be review manually by the person that raised the issue initially.

Our task board:

Additionally, we use tags to classify issues by other criteria:

User Reported: Whether or not this issue has been reported by users in the production environment, this normally means it requires extra attention. Estimation: Whether or not this issue requires additional research and estimation before being added to the Backlog. Project Number: Project Number which relates to cost tracking and invoicing.

Environments and our code

We use long-lived 2 branches: master and development and features branches to create Merge Requests (Pull Requests in Github).

Our rules dictate the there must be frequent merges from development to master, we call that “release merges” but they only mean this is code that is considered ready for release. Those branches have an impact when and how our code is delivered to each environment.

We use 4 environments (in addition to each team member local), each with a particular responsibility:

DEV Environment: All code that is merged to development is immediately deployed to this environment. And every time there is a release to development a new “SNAPSHOT” git tag is created.

QA Environment: Any member of the team can deploy here from one of the “SNAPSHOT” tags. It is used by reviews and exploratory testing.

STAGE Environment: Every time there is a release to master a new “RELEASE” git tag is created, which is the only way to deploy to STAGE.

Our STAGE environment connects to production systems (most important of all is the payment gateways) so it, in fact, possible to pay (!) for products using this environment.

LIVE Environment: Production environment, we release to it every 2 weeks or more often.

Note on hotfixes: sometimes they are unavoidable, in this case, we create a Merge Request directly to master.

Learning & conclusions

Like a sturdy dandelion, our project is a successful Agile project in an environment that is not friendly to iterative development.

Also, much like our dandelion, our project cannot be compared to one of the other projects with more resources or which exist in a more “product-oriented” environment, in which time-and-materials billing is the norm. However, our users and team members are satisfied, and our customer respects us and keeps working with us.

Agile’s foundation is automated testing

Without a question, the only reason we are able to maintain a stable release cycle of 2 weeks, is the team discipline (mostly driven by the developers!) of keeping an up to date suite of unit and black-box integration tests (Selenium based).

We still must do manual testing but it is often a simple smoke test, or for browser-specific implementations.

Rules are important, but habits are more important

I would consider our process to be “habit-driven”. Why is our process also habit? Because we will all default to follow our process most of the time “out of habit” and for this reason, this process must be built over time.

However, when the process doesn’t help our goals, we “skip a day” of our habit.